Last week, at a sophisticated business dinner with a client, I had an unusual experience. The speaker was a political journalist. He was intelligent, articulate, funny and engaging. I warmed to him and I respected him. But I disagreed with almost every word he said.

This caused me to reflect on the fact that I need more experiences this like this in my life right now – in which I can respect a person without having to agree with them. The experience was powerful precisely because his words opened up my mind to other ways to think about the issues he spoke about that I wouldn’t have otherwise considered. I internally agreed to disagree, but to listen with interest and openness. As a result, I found my perspective shifted slightly; my solid views were more amenable to an alternative truth. And it struck me that this is, ultimately, an approach that – now more than ever – we need our leaders to embrace.

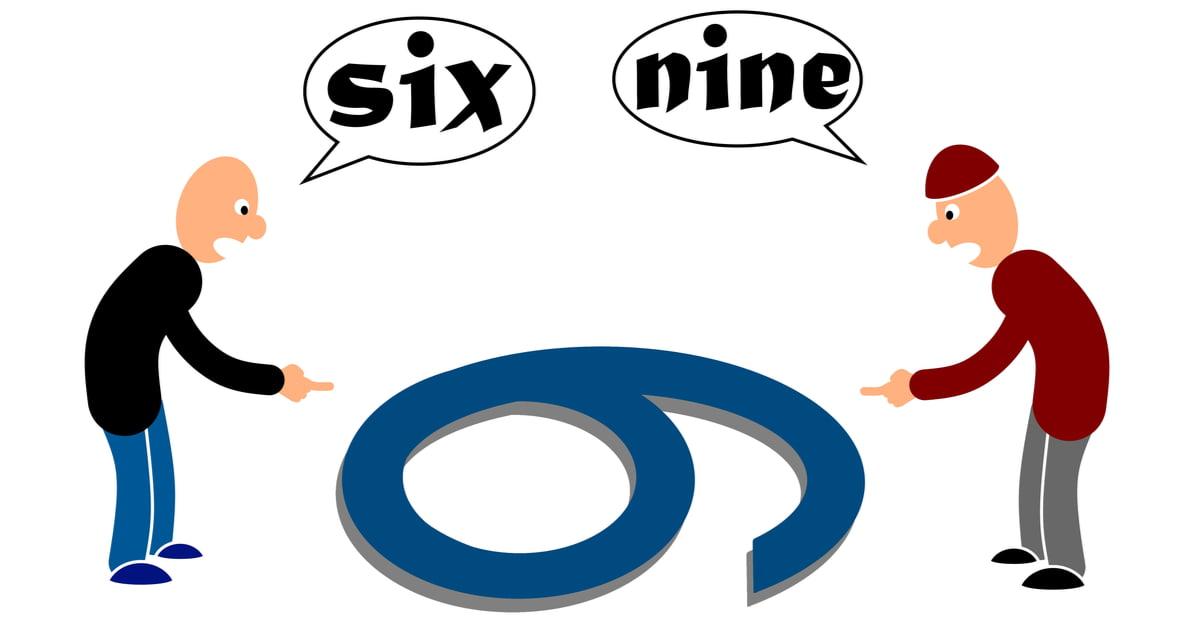

It contrasts deeply with our usual way of operating. Think about our political debates in the UK for the last three years. Typically, we surround ourselves with people who hold the same views as us, creating a perfectly tuned echo chamber, which tells us how right ‘we’ are and how wrong ‘they’ are. But it leads only to division and distortion. It makes it easy to see the other as bad or wrong rather than another whole person, but with a different perspective.

What if we had the humility to accept that we don’t have all the answers; that the answers that we have might be wrong; and that those with insightful new perspectives might be located in the most unusual and humblest of places? This attitude has the potential to shift the dominant either/or narrative in our culture to an altogether more fruitful place.

It’s the same inside our organisations. Teams pit themselves against other teams for scarce resources, and power struggles erode trust and collaboration within executive teams. The economist and diplomat John Kenneth Galbraith summed it up when he said: ‘Faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.’

And yet, our own experience tells us that we get it wrong as often as we get it right. Think back to a time in your life when you received criticism from a boss, colleague or friend, or missed out on an opportunity that you thought you were perfect for. Typically, in time, our distress about the event lessens and our views about it soften and change. Perhaps we realise that our colleague had a point; that our reaction was unreasonable or that the opportunity wouldn’t have been right for us after all. We are indeed wise after the fact.

What has happened here? Usually, the reflections that we make over time help us to shift our perspective from our own, first-person view, to a wider, more nuanced perspective. We’re able to expand our personal viewpoint to include the wider context in which the event took place, and see our position as only one of many. We locate ourselves as part of the wider action, rather than seeing ourselves at the heart of the matter. What if there was a way that we could tap into this wisdom, not after the fact, but when we actually need it? This would be a powerful resource for us to use as leaders and as citizens. There is, and it’s known as perspective-taking. But it’s a skill and it requires practice.

What is perspective-taking?

Our perspectives are shaped by a number of factors. Our experiences, values, judgements, information, needs and desires all affect our outlook. Our outlook will also be impacted by our ability to deliberately step out of it and take on multiple perspectives so that we can more fully understand what’s going on in a given situation. Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linksy at Harvard University advocate that leaders should operate both in and above the fray: that is, move backwards and forwards between being in the action and stepping back and observing the action. They use the metaphor of ‘getting off the dance floor and onto the balcony’ where you can observe the action to better understand what’s going on.

You are on the dance floor when you are in the action: a necessary place for leaders to be on occasion. But to understand what’s happening there you need a different perspective. That’s when you get onto the balcony. It provides distance and an alternative vantage point.

Richard Boston and Karen Ellis outline four increasingly sophisticated ways of shifting our perspective. Each one building and expanding on the others, bringing in more of the context and broadening our perception of the factors influencing what’s going on.

Four perspectives

1st perspective – our own view

In the first-person perspective, we’re concerned only with our own point of view: ‘this is what I think; this is how I feel.’ We are caught up in our own story with little regard for others. There are times when this is a necessary stance; but ultimately if we can’t move out of our own take on things, we’re unlikely to be able to take on the views of others or be able to have a fuller viewpoint of what’s going on.

Most well-developed adults are able to move from this limited perspective to one that can at least try to understand the thoughts and feelings of the other person. This is the second-person perspective and it helps us to understand what’s going on for the other person. We get there not by imagination, but by inquiry. It’s only by asking others their views – along with their thoughts, feelings and emotions – that we can assume with any certainty that we understand what’s going on for the other person. We all have examples of where we did this and were surprised by what we discovered; and we can all recall other times when we didn’t bother to ask: either not caring enough to know, or by defaulting to our own assumptions.

2nd perspective – the other’s view

In this second person-perspective you can take the stance of: ‘I can understand and appreciate how you feel – even if I don’t agree.’ By helping us to understand others better, it helps us relate better to them. This represents a significant shift in our ability to be effective. We become better at predicting what might happen in a situation; we are better able to appreciate others. And since we now understand their actions and motivations better, we can in turn influence them. Crucially, this second-person perspective helps us to build empathy – the relational glue that holds us together.

3rd perspective – the outside view

As powerful as it is, on its own the second-person perspective doesn’t provide us with enough distance to understand what’s happening in a situation. Our own view is limited – and by extension other peoples’ views are also limited. Taking a step back further still – to a third-person observer perspective – allows us to take a more objective position on what’s going on; less caught up in the personal drama of the individuals. It’s from here that we are able to take on multiple perspectives and look at a situation through the eyes of several different people or stakeholders. It’s in this third-person perspective that we’re able to move above the content of the problem to look at its structure, and in so doing we’re better able to work with it to solve it.

For example, imagine you are being constantly caught up in the interpersonal dramas of two highly strung colleagues. From a first-person perspective you might feel frustrated and annoyed. From a second-person perspective you might be able to empathise because the amount of work loaded onto one highly able colleague is causing resentment of the other colleague, who has less to do. You can also see the perspective of this other colleague, who is resisting taking on more work due to his other commitments. In the third-person perspective you might ask, ‘What’s really going on here?’ It’s in this space that we lift ourselves up to take the helicopter view. Crucially, we resist ‘taking on’ one or other of the points of view of the individuals involved and instead look at the interaction and the situation without the biases, filters and mind traps that are inevitable when we occupy either the first- or second-person perspective. This ability to take on multiple perspectives provides a breadth and depth to our understanding that we’re unable to gain when we only look for our own or the other person’s point of view.

4th perspective – the meta view

Now envisage that above all of the noise of multiple perspectives, there’s a deeper structure to what’s going on. This is the fourth-person perspective. Perhaps the tension between these colleagues is happening because poor performance-management structures mean that able people are loaded with more and more work without addressing the underlying issue that other employees are not carrying their weight. Or perhaps it is due to an avoidant style of management at the leadership level.

The ability to take this meta-perspective is what’s required in the fourth-person ‘witness’ perspective. From this stance, we’re aware of the context in which relationships play out. We see that there is a deep structure to the nature of the problem and that the people involved are often unwittingly caught up in that structure.

Becoming more practiced in shifting between different perspectives is a critical leadership skill. The people we lead need us to be in the action at times, but they also require of us the ability and willingness to move to a more holistic perspective; actually ‘seeing’ the problem differently.

The political journalist at the dinner didn’t shift my political affinities; but his talk helped reminded me that there are other, equally valid views that I should keep in mind.

References

Boston, R. & Ellis, K. (2019) Upgrade: Building your capacity for complexity. London: LeaderSpace.

By Jacqueline Conway…

Dr Jacqueline Conway works with CEOs and executive teams as they fully step into their collective enterprise-wide leadership, helping them transform their impact and effectiveness.

Jacqueline is Waldencroft’s Managing Director. Based in Edinburgh, she works globally with organisations facing disruption in the new world of work.